Tent Schools Better than Nothing: Displaced Syrian Children Insist on Education

By: Murad Quatly

From inside a cloth tent, erected on muddy ground, rise sounds full of life despite a surrounding that calls for nothing but despair. Here, alphabetic letters are written and erased; numbers are added and subtracted; songs resound, and dreams are drawn on notebooks’ pages.

Every morning, children set out from their tents in several camps in northern Syria to another tent inside these camps. Instead of calling it a tent, they call it a school. In fact, it has nothing similar to the schools the world knows apart from its being called so.

Most of the pupils at “tent schools” sit on the floor. They have no chairs; no big boards to write on; no windows through which the children peek to see their schoolmates playing in the yard; and no walls to prevent the cold from penetrating the children’s tender bodies.

Nevertheless, children in northern Syria’s camps insist on studying, albeit in a tent.

Ghazal, a 6-year-old girl, is one of the pupils who attend the so-called “educational tent” in the Al-Zohour camp. She and other girls sit on the ground for hours. Not only does displacement brings them together, but their love for drawing, mathematics, and playing among the trees that surround their tent school.

In her life, Ghazal had never known a school other than this tent. She believes that schools have always been similar to her current one in the tent. However, she told us that she loves her school.

The United Nations estimates that around 40 percent of Syria’s school infrastructure has been damaged or destroyed during the war, depriving millions of children of an opportunity to complete their education.

Northern Syria had been repeatedly subjected to bombings and turned into battlefields that had a major role in destroying schools. To cope with that, initiatives were launched by the residents of the camps scattered throughout northern Syria to establish schools to offer whatever education they can to their children.

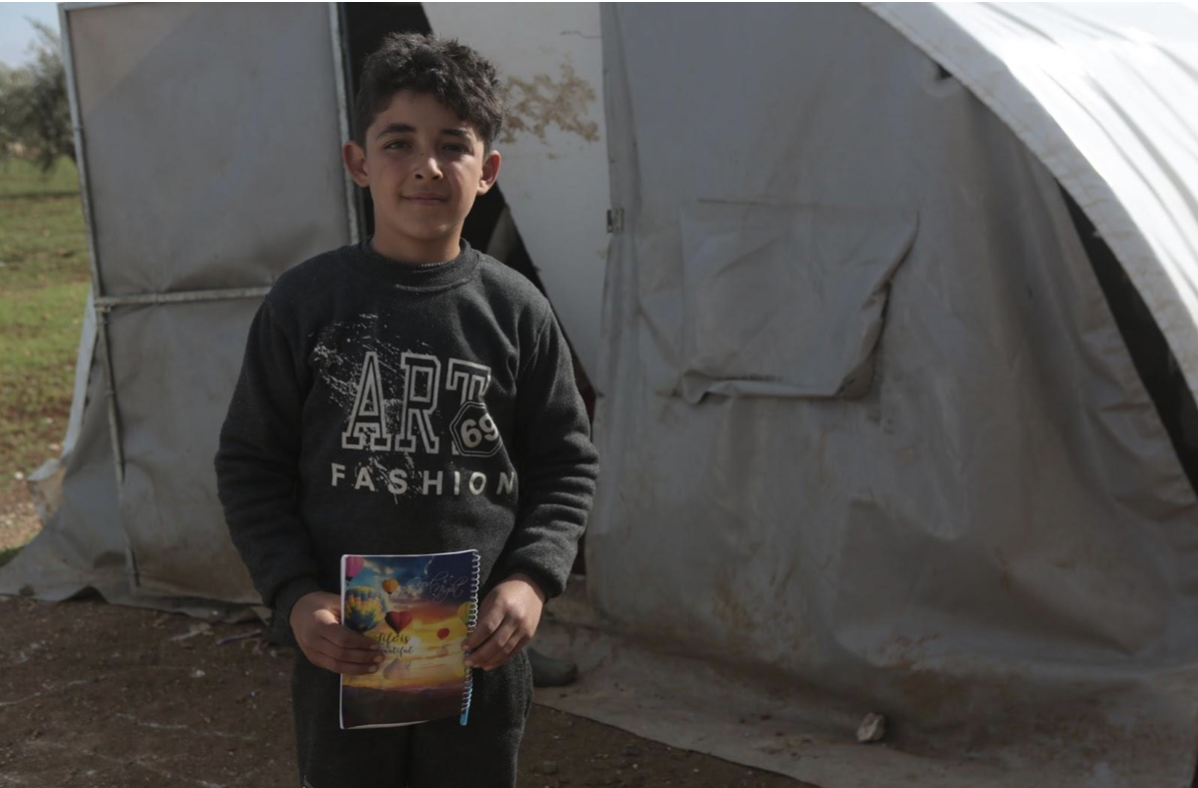

In Al-Shat Camp, Khair Ali Mustafa, an 11-year-old boy, studies in a tent with a number of other camp children. He feels sad that his “school” has no name. He described it as a mere tent.

Mustafa complains about the mud that spreads all the way long to the tent on winter days. “Our life in the camp is difficult,” he says, yet he shows great determination to complete his education so that learning might help him improve his and his family’s economic conditions once he grew up.

Mustafa misses the school he used to go to in his village before it was bombed and he was forced to move to a camp in northern Syria. Back there, he and the rest of the children could at least go to the village school, even if it was freezing cold.

In their current tent school, however, they have not to go to school if it is cold and when it rains.

Mustafa dreams of studying law at the university and becoming a lawyer. “I want to defend people’s rights,” he said enthusiastically.

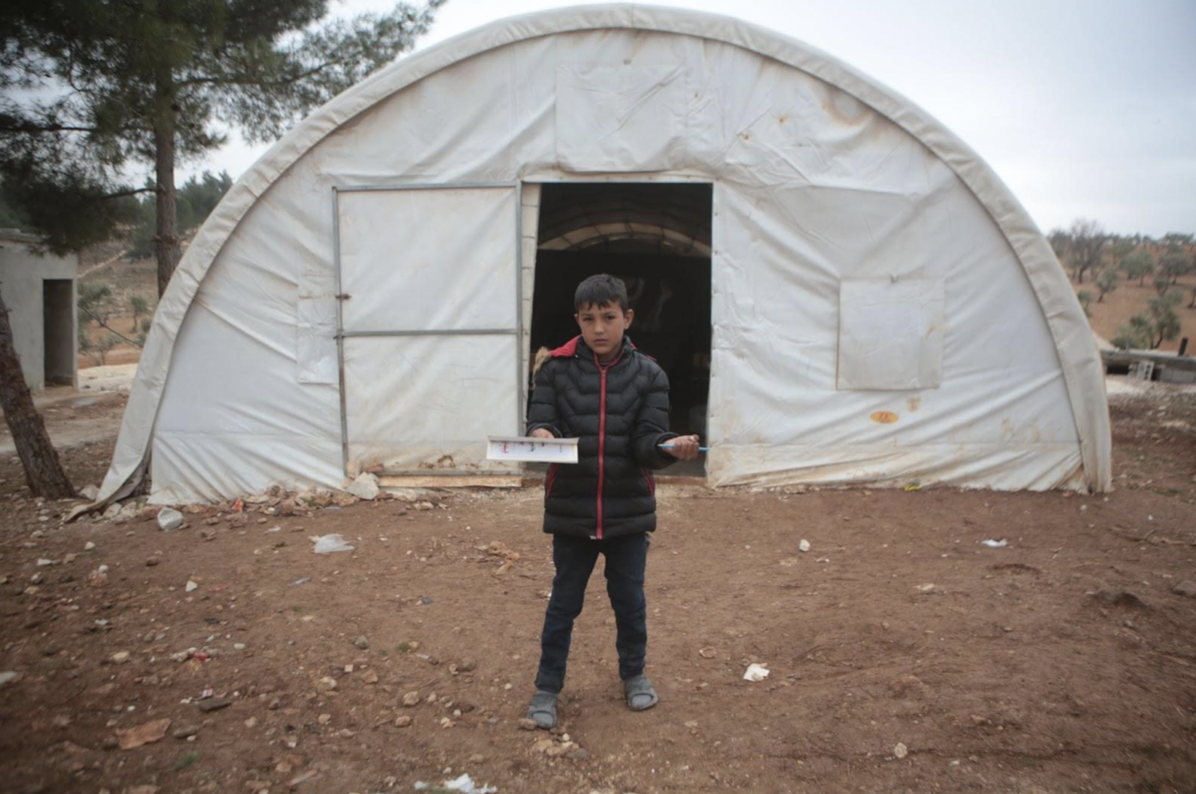

In another camp in northern Syria, a child named Mustafa Sabri builds his dream day after another, to become a doctor. Despite his feeling uncomfortable, he spends hours daily in the tent learning. In the end, having a modest “school” is better than nothing, he thinks.

The 10-year-old boy lives in the “Al-Ta’awun Camp.” Like the case for other children, wintertime is a nightmare for him. For him, rain and snow mean that he will be deprived of going to the “educational tent” for days.

In the same camp where Sabri lives, Ruaa, 12, also attends the tent to learn. This little girl gives hope to other children for she is not only a student who sits at the desks with them, she sometimes becomes their teacher. She helps her schoolmates to better understand the lessons.

With determination, Ruaa told Tiny Hand about her desire to continue her education until she gets a university degree in medicine. Although the tent lacks the basic requirements for education, the little girl loves her desk, notebooks, and pencils.

Like other children, Ruaa complains about the harsh weather. She feels sad when her friends don’t come to the tent when the weather is bad.

It is feared that the harsh living conditions and the difficulty of education will affect the psyche of children in the camps. According to the UNICEF, one in eight children per classroom requires specialized psychosocial support to achieve proper education.

The United Nations also confirms that over 2 million children – over one-third of Syria’s child population – are out of school and 1.3 million children are at risk of dropping out.

The situation of Syrian children in neighboring host countries is not any better, as the UN estimates that over 800,000 children remain out of school.

In Jordan, for instance, 38% of Syrian children aged 15 to 17 are not enrolled in schools. The international organization attributes dropping out or not enrolling in school to distance, cost, overcrowdings, and exposure to bullying.

In the end, the children of northern Syria’s camps want to live like the rest of the children around the world. They also have dreams and hopes that they strive to achieve despite their poor life and dire economic conditions.

Related Posts

Surviving war in Damascus

In the heart of Old Damascus,, where life is marked by challenges and hardships, lives Maya. At just 14 years old, she carries burdens far beyond her years. Surviving war in Damascus Maya's Journey: Becoming the Strength of My Family Through Collecting Cardboard Enter keywords…

March 10, 2025Tiny Hands, Heavy Burdens: A Child’s Life on the Construction Site

At five in the morning, we met Issa in his modest, rural home in al-Karamah area of the Raqqa countryside. The early breeze bit into our faces as Issa finished breakfast with his brothers and father. Dressed in a red shirt, he had pulled on a light cotton jacket to shield himself from the morning chill….

March 10, 2025