‘People think it’s magic’: how one of Brazil’s poorest cities gets its best school results

Report from: The Guardian

As you approach the city of Sobral in north-east Brazil, the road worsens. Huge pot holes slow traffic to a crawl. The heat is suffocating, even worse when there is no cloud cover.

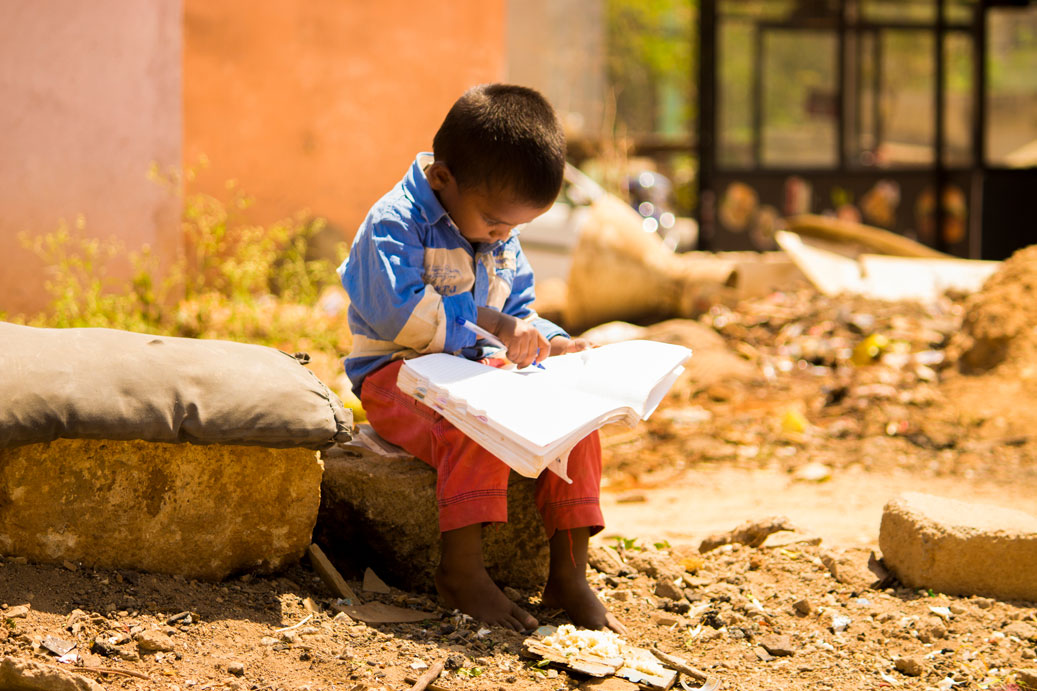

Sobral is poor. Jobs are scarce, salaries meagre, gangs the only option for many. For children, it’s a tough start to life. Ana Farias, headteacher of an early-years school in a low-income neighbourhood controlled by a gang, knows this only too well. Some of her students wouldn’t eat if it were not for free school meals.

Farias and her colleagues often hear stories of home life; some children have to accompany their mothers who sell sex at night. “It’s a challenge but it motivates me to be here every day. We want to make a difference in their lives,” she says.

This is one of the last places anyone would expect would be a paragon of educational excellence. Yet, Sobral has gone through an extraordinary metamorphosis and is now the best place in Brazil to get a state education.

The city comes top of 5,000 districts in Brazil’s education development index. Fifteen years ago, it was ranked 1,366th. Since 2015, literacy rates have risen from 52% to 92%, and the number of families living in extreme poverty has declined by 89%.

This is a stunning turnaround in a country beset by income inequality and poor literacy rates: half of state-educated students are still illiterate by the third grade.

So what has been Sobral’s secret to success? The mayor, Ivo Gomes, says: “We have reached this position because this is a 23-year-old project that has surpassed changes in mayors and secretaries of education. People think it’s magic and it’s not. It is persistence and a lot of hard work.”

In 1997, the movement to improve education in Sobral began with renovating school buildings and furnishing them with computers and other resources. Public spending on education was boosted.

In the past, politicians had commonly rewarded allies by handing out government jobs, including headteacher posts to people who could barely read or write. This practice was stamped out.

There was a crackdown on truancy; today families are called if their children don’t turn up to school. Newly qualified teachers now undergo a preparatory internship and all teachers, regardless of experience, receive on-the-job training for a day each month. Every term there is a bonus system for teachers whose students perform well in assessments.

Student welfare is a high priority; pupils receive two free school meals a day and there are plans to hire a mental health professional in each school.

All this has led in part to the success of former students such as Chelton Santos, 22, and his sister Maria, 20. The siblings live with their parents and grandmother in a poor and dangerous area. The family have survived on one minimum wage (now $258 a month) for many years.

“I grew up seeing gang fights,” said Chelton Santos. “I had to face poverty and violence. My parents took good care of us but we had financial difficulties, and had to take out loans.”

Despite a difficult upbringing for the pair, the future is looking bright: Santos is studying law at university and his sister is working as an office clerk to save money to study medicine. They are determined to succeed. Maria says: “My dream is to be a doctor. I’m going to get there. I’ve seen my mother suffer with health problems since I was a child and now I want to help the poorest in society.”

Their mother, Eliane, is hopeful about her children’s future: “I never believed that one day my son would be studying to be a lawyer at university. We did everything we could to keep [the children] in school. I wanted to give them a nicer place to live … it’s dangerous here. God willing, they’re going to move from here to a better life.”

Sobral’s success is now being replicated across the country. Clodoveu Arruda, a former mayor of the city, who oversaw a large part of the transformation in the education department, has teamed up with the Lemann Foundation to spread best practice. So far they have worked in 25 municipalities across five states.

Not everyone in Sobral is content with what has been achieved, however – they are hungry for further success. The mayor, Gomes, says: “Being the top in Brazil doesn’t mean much if you look at the rest of the world. Brazil is not very well positioned in the [international educational] Pisa rankings … This is what we are running after now.”

Related Posts

We don’t expect any legal issues since the family is Syrian”: A Turkish network in Istanbul forces families to place infants in incubators to make money

Led by Turkish doctor Fırat Sarı, a network of doctors, nurses, and ambulance drivers, has been accused of systematically admitting newborns into incubators for extended periods, even when their health did not require it. The scheme, allegedly driven by financial motives, exploited vulnerable families, unnecessarily prolonging the infants’ time in intensive care.

…

October 21, 2024“Yemeni Women Feed Their Children with Tea” “Amid Lack of Milk

The over seven-year-long conflict in Yemen has caused the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, said the United Nations, with a significant economic deterioration affecting most of Yemen’s population, widespread hunger, poverty and unemployment, and the spread of acute and severe malnutrition among under-five children….

August 31, 2022