Children of African Migrants Looking for Decent Life in Morocco

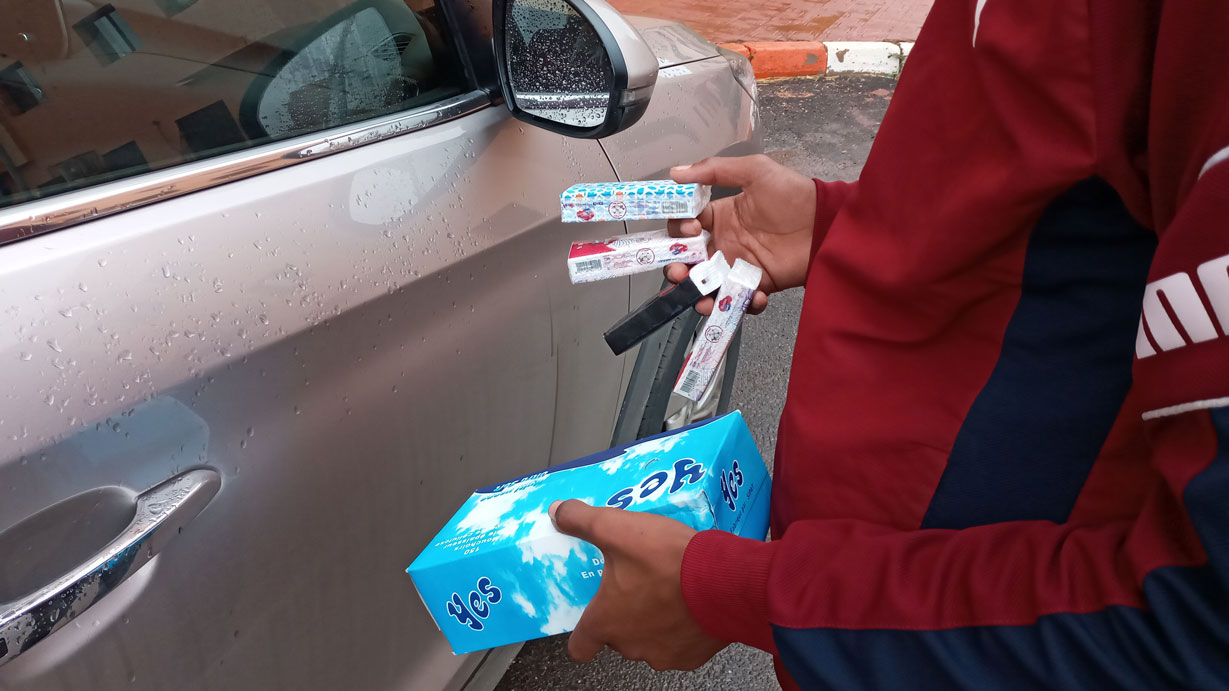

Tissues! Tissues! Would you like to buy tissues from me, sir?” Uliakar chanted in colloquial Moroccan Arabic but in a foreign accent as he crosses the cars waiting for the traffic light to turn green.

Uliakar, too, is waiting for someone to buy a tissue box from him. Since he came to Morocco, the young Senegalese guy has been trying to look for a job that can offer him a good life; but he has failed to find one.

Out of anxiety, Uliakar refused to speak to Tiny Hand for fear of deportation from Marrakesh. He is a minor carrying neither identity documents nor a residence permit.

After receiving repeated assurances that his identity will not be disclosed, 17-year-old Uliakar expressed a deep longing for his parents and younger siblings. “I came from a beautiful village on the outskirts of Senegal’s capital city, Dakar, and I have been here over the past 8 months,” he told Tiny Hand.

Next Station He Has Never Reached: Spain!

Poverty haunting his family made him grow up before the time for maturity comes.

He came to Morocco in April 2019 hoping that he might find a way to get from there to Ceuta, a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Uliakar’s dreams have been smashed by reality: his journey to reach the Moroccan city was not as easy as he had previously thought; and his requests to work in shops and restaurants were rejected by their owners because he is a foreigner and a minor.

During summer months, young Uliakar used to sleep on the streets of Marrakesh although they become scorching hot. His back bag is everything he brought with him from his home country.

He spends his day wandering around in the streets selling tissues or carrying boxes containing vegetables and fruits in exchange for a few ones or waiting till someone gives him alms out of generosity.

National Immigration and Asylum Strategy

In November 2013, Morocco launched the National Immigration and Asylum Strategy facilitating migrants’ inclusion in the educational system in the country, guaranteeing that they receive treatment in the Moroccan hospitals, granting them housing rights in accordance with the Moroccan laws, giving them legal and humanitarian support, and allowing them opportunity to apply for jobs.

23,000 irregular African migrants benefited from this initiative. The second phase of this program was launched at the end of 2016. Then, decision was taken for migrants to be issued three-year, rather than one-year, permits upon expiration of their previous residence card.

According to the UNHCR in Morocco, the National Immigration and Asylum Strategy has achieved success four years after its formulation at least for the refugees; since it guaranteed their physical and legal protection.

The number of migrants registered at the UNHCR in Morocco reached 5000 persons and they were given access to health, employment and education services, 82% of whom are children registered at public schools.

Brancilia is a girl who came to Morocco from the Democratic Republic of the Congo accompanying her mother and two of her siblings; yet, she is not one of the migrants’ children who are registered at the public schools in the kingdom.

The girl immigrated from Congo after unrest had triggered there leading to the fleeing of around two million people since January 2017 thanks to the violence escalating in the republic.

“I Sought Refuge in Morocco after My City Destroyed”

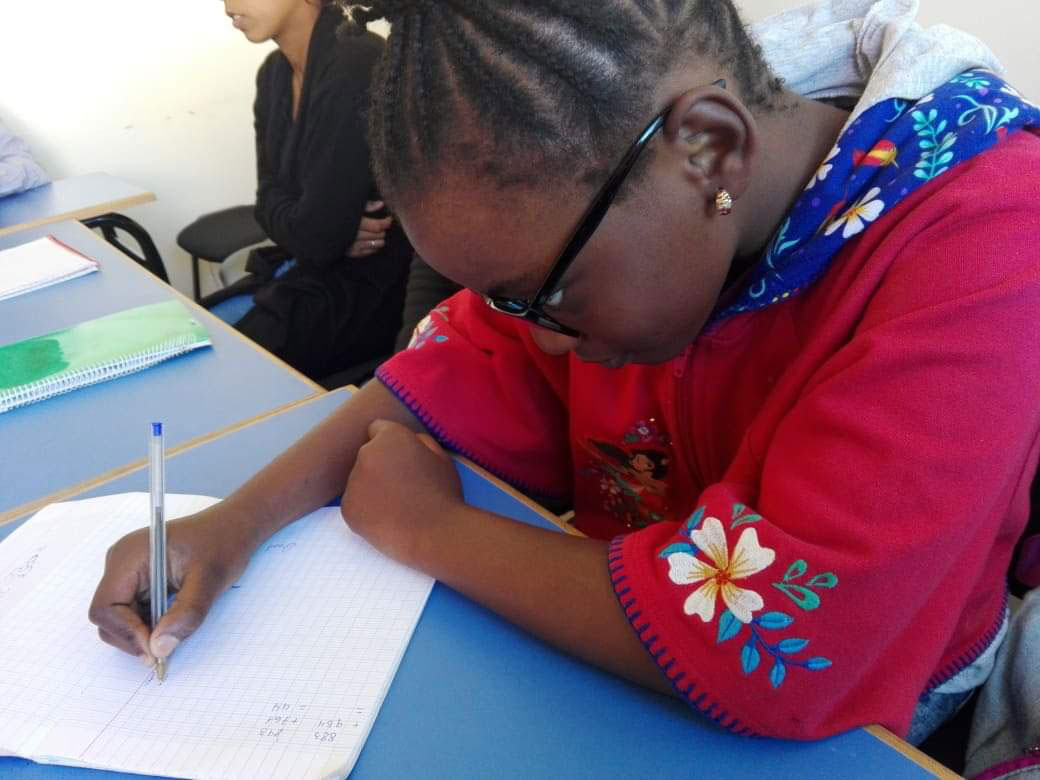

“I arrived in Morocco two years ago. I have good Moroccan friends who go to school every day. I learn to speak and read colloquial Moroccan Arabic only twice a week,” said 13-year-old Brancilia with sorrow.

The girl recalled memories of her school and home city which was destructed at the hands of the armed militias who stayed at classrooms. She stressed that she was a clever student and that she used to receive regular and good-quality education in her country.

When her turn to speak came, Brancilia’s mother affirmed that her family’s conditions had been perfect in Congo and that her children had used to continue their education at the finest schools. But when war erupted, everything went upside down and thousands of citizens decided to flee the country and move to another one.

Mrs Jane Zankand, also known as Mama Jeanette, retreated into a long silence allowing her uncontrollable tears to stream down her face. Meanwhile, Brancilia was giving her mother a sad look saying, “I don’t want to stay at home. I wish to continue my education because attending lectures only four hours a week is not enough!”

Mama Jeanette, Mother of All African Migrant Children

In order to prevent the future of African children from becoming gloomy, Mama Jeanette has become a mother for all of them. Although she has not stayed for long in Morocco, she has become a consultant for the African migrant families who desire to educate their children.

Brancilia aspires to attend classes 5 days a week at a Moroccan public school along with her friends who live in the same neighborhood with whom she enjoys chatting and playing.

However, the aspirations of both the girl and her mother were smashed by the reality that schools require carrying out many administrative procedures. “Even the procedures required to provide the documents needed to apply for the residence card are complex and tiring!” Mama Jeanette told Tiny Hand.

African Migrant Children Waiting for Chance to be Enrolled in Public Schools

Brancilia is not the only girl who receive education at “Al Amal,” an association providing non-formal education. Other Senegalese and Malian children also attend 2-hour classes there, twice a week.

These students sit shoulder to shoulder listening to their Moroccan teacher who is eager to teach them the colloquial Moroccan Arabic so that it can be easier for them to communicate and interact with society. He also teaches them topics related to the Moroccan culture and traditions.

14-year-old Jessi, 9-year-old Ghaioun, and 11-year-old Saki are among the children of African migrants who were brought to Morocco. They wish to enjoy good living conditions, have a better future, and be given the opportunity to be enrolled in public schools with longer credit hours to enjoy the learning experience.

Related Posts

The Stories and Names of Over 60 Children Executed in the Syrian Coast Massacres

The Tiny Hand team, in collaboration with Daraj, collected over 50 testimonies documenting the killing of 60 children during the massacres in the Syrian coastal region. To this day, the perpetrators have not been held accountable. These were “unidentified” killers — witnesses interviewed could not determine their factional affiliations, alongside others from armed civilian groups who arrived in the coastal area. Amnesty International has called for their prosecution, considering the events of March 6, 7, 8, and 9, 2025, to be war crimes….

April 30, 2025Abandoned Children: Foster Care in Northern Syria Amidst the War Years

All names in this investigative report have been changed to protect the safety and security of those involved and to ensure the identities of the foster families who have taken in some of these children remain confidential. Confidentiality is a fundamental principle in the success of this mission, as safeguarding the identities of both the children and the families providing care is critical, particularly in regions affected by ongoing conflict and instability….

March 12, 2025