Buying a baby on Nairobi’s black market

Report from: BBC

Somewhere, Rebecca’s son is 10. He could be in Nairobi, where she lives, or he could be somewhere else. He could, she knows in her heart, be dead. The last time she saw him, Lawrence Josiah, her firstborn son, he was one. She was 16. It was about 2am one night in March 2011 and Rebecca was drowsy from sniffing a handkerchief doused in jet fuel — a cheap high on the city’s streets.

She sniffed jet fuel because it gave her the confidence to go up to strangers and beg. By the time she was 15, Rebecca’s mother could no longer support her or pay her school fees, and she dropped out and slid into life on the street. She met an older man who promised to marry her but instead made her pregnant and left. The following year Lawrence Josiah was born, and Rebecca raised him for a year and a few months until she closed her eyes that night and never saw him again.

“Even though I have other kids, he was my firstborn, he made me a mother,” she said, fighting back tears. “I have searched in every children’s centre, in Kiambu, Kayole, and I have never found him.”

Rebecca still lives on the same streets in Nairobi. She is small, with sharp cheekbones and short, tightly braided hair. She has three more children now — girls aged eight, six, and four. The youngest girl was grabbed once, she said, by a man who’d been hanging around the area. He claimed the barely one-year-old girl had asked him to buy her a drink. Rebecca followed him to a car afterwards, she said, where a woman was waiting. The next day, he was back.

You do not have to look hard to find similar stories around the streets where Rebecca lives, alongside other unhoused Nairobi residents. Esther’s three-year-old son disappeared in August 2018. “I have never been at peace since I lost my child,” she said. “I have searched for him all the way to Mombasa.” It’s been five years since Carol’s two-year-old son was snatched in the middle of the night. “I loved him so much,” she said. “I would forgive them if they would just give me back my child.”

Vulnerable women are being preyed on in Nairobi to feed a thriving black market for babies. Over the course of a year-long investigation, Africa Eye has found evidence of children being snatched from homeless mothers and sold for massive profits. We uncovered illegal child trafficking in street clinics and babies being stolen to order at a major government-run hospital. And in an effort to expose those abusing government positions, we arranged to purchase an abandoned child from a hospital official, who used legitimate paperwork to take custody of a two-week old boy before selling him directly to us.

The baby-stealers range from vulnerable opportunists to organised criminals — often both elements working together. Among the opportunists are women like Anita, a heavy drinker and drug user who herself lives on and off the street, and makes money stealing children from women like Rebecca — targeting mothers with infants under the age of three.

Africa Eye found out about Anita through a friend of hers, who wanted to remain anonymous. The friend, who asked to be called Emma, said Anita had different methods for snatching children on the street.

“Sometimes she will speak to the mother first, to try and see if the mother knows what she plans to do,” Emma said. “Sometimes she will drug the mother, give her sleeping pills or glue. Sometimes she will play with the kid.

“Anita has a lot of ways to get kids.”

Posing as potential buyers, Africa Eye set up a meeting with Anita in a pub in downtown Nairobi frequented by street sellers. Anita told us she was under pressure from her boss to steal more children, and she described a recent abduction.

“The mother was new to the streets, she seemed to be confused, not aware of what was going on,” she said. “She trusted me with her child. Now I have the child.”

Anita said her boss was a local businesswoman who bought stolen babies from petty criminals and sold them for a profit. Some of the customers were “women who are barren, so for them this is a kind of adoption,” she said, but “some use them for sacrifices”.

“Yes, they are used for sacrifices. These children just disappear from the streets and they are never seen again.”

That dark hint echoed something Emma had already told us, that Anita said some buyers “take the kids for rituals”.

In reality, once Anita has sold a child on, she knows little about their fate. She sells them to the businesswoman for 50,000 shillings for a girl or 80,000 shillings for a boy, she said — £350 or £550. That is roughly the going rate in Nairobi to steal a child from a woman on the street.

“The businesswoman, she never says the business she does with the kids,” Emma said. “I asked Anita does she know what the woman does with them, and she told me she could not care less whether she takes them to witchcraft or whatever. As long as she has money, she does not ask.”

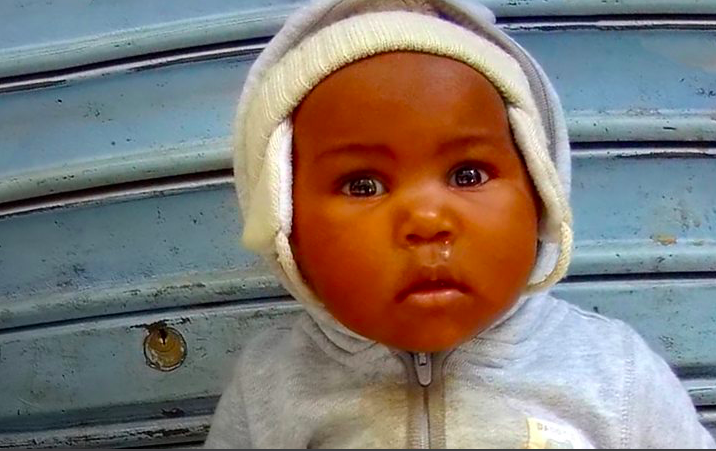

Soon after the first meeting, Anita called to arrange another. When we arrived, she was sitting with a baby girl who she said was five months old and she had just snatched moments before, after winning the mother’s trust.

“She gave it to me for a second and I ran away with it,” she said.

Anita said she had a buyer lined up to purchase the girl for 50,000 shillings. Emma, our source, attempted to intervene, saying she had been introduced to a buyer who could pay 80,000.

“That is good,” Anita said. “Let’s seal the deal up for tomorrow.”

Related Posts

The Stories and Names of Over 60 Children Executed in the Syrian Coast Massacres

The Tiny Hand team, in collaboration with Daraj, collected over 50 testimonies documenting the killing of 60 children during the massacres in the Syrian coastal region. To this day, the perpetrators have not been held accountable. These were “unidentified” killers — witnesses interviewed could not determine their factional affiliations, alongside others from armed civilian groups who arrived in the coastal area. Amnesty International has called for their prosecution, considering the events of March 6, 7, 8, and 9, 2025, to be war crimes….

April 30, 2025Abandoned Children: Foster Care in Northern Syria Amidst the War Years

All names in this investigative report have been changed to protect the safety and security of those involved and to ensure the identities of the foster families who have taken in some of these children remain confidential. Confidentiality is a fundamental principle in the success of this mission, as safeguarding the identities of both the children and the families providing care is critical, particularly in regions affected by ongoing conflict and instability….

March 12, 2025